The announcement of the aborted (postponed?) European Super League in April represented the end of one con and the attempted beginning of another. The subsequent reaction only reiterated the adage that history is written by the winners.

You already know enough. So do I. It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.

— Sven Lindqvist, “Exterminate All the Brutes”: One Man’s Odyssey into the Heart of Darkness and the Origins of European Genocide.

The 2020/21 European football season was played out for the most part behind closed doors as the Covid-19 pandemic continued to wreak havoc with daily life across the continent. Perhaps as a consequence, unlikely stories in Europe’s top domestic competitions abounded to a degree that we hadn’t seen in some time.

League wins for Atlético Madrid, Inter and Lille OSC in Spain, Italy and France respectively were accompanied by wretched campaigns for reigning champions such as Liverpool and Juventus (the latter of whom were going for ten-in-a-row in Italy), although both of those clubs recovered in the closing weeks of the season to secure Champions League qualification. Villareal won a first ever major trophy with their Europa League triumph in Gdańsk, Leicester City a first ever FA Cup with their final victory over Chelsea, and second division Holstein Kiel made it all the way to the DFB-Pokal semi-final having knocked out the mighty Bayern Munich along the way.

The Champions League, however, provided a grim sense of familiarity, with thirteen-time winners Real Madrid joining the oil barons of Chelsea, Manchester City and PSG in the semi-finals. And then, straddling perfectly that ample divide between predictable and shocking like two cheeks of a mammoth arse, came the plop of the European Super League (to which I will subsequently refer as “ESL” for the sake of brevity).

As word began to spread on Sunday 18th April 2021 that an official deal had been struck between 12 founding members that included the club I have supported since I was 7, my own dominant feeling was one of resignation. Apparently, I was the only one who felt that way. While I was here feeling resigned to a fate pre-ordained by about 40 years’ worth of greed and chicanery at the top of the sport, the rest of the football community were not so much joining together as they were jostling and trampling each other in the race to be the most shocked and offended.

What followed over subsequent weeks was a stampede of righteous condemnations and hot-takes that resembled the front of the line on Black Friday or the running of the bulls in Pamplona. Whether it was the assorted governing bodies of European football, the media led passionately by the likes of Gary Neville and Jamie Carragher on Sky Sports, the veritable cavalcade of former players, managers and club officials queuing up to give their opinions, the likes of Leeds United who left shirts with the slogan “UEFA Champions League: Earn It” in Liverpool’s dressing-room ahead of their match at Elland Road on 19th April (as if the visiting players had anything to do with the decision to join the ESL, or as if Leeds would have acted any differently if they were big enough to be considered for such a competition), or supporters protesting outside stadiums up and down the country (and also inside Old Trafford), acceptance of the inevitable was the last thing on everyone’s minds.

I would have admired this stubborn refusal to surrender if it wasn’t largely built on foundations alternately consisting of self-preservatory cynicism and breathtaking (perhaps performative, in some cases) naivety. A prime example is Neville, who was particularly outspoken on the subject of both the ESL and the six English clubs who sought to join it from the moment it was announced, two of them in particular. “Maybe I’m being naive,” he began on Sunday 2nd May during the protests at Old Trafford, “but Manchester United and Liverpool should be acting like the grandfathers of English football, demonstrating compassion, spreading their wealth through the family and being fair.” Compassion? Fairness? In football? What year is this?

Given that he has appeared weekly on Sky Sports since 2011 and represented Manchester United for the best part of two decades before that, we have visual proof that Neville hasn’t been living under a rock, in a cave, on some far-flung planet for the past 30 years. Furthermore, a man typically doesn’t get a foothold in property development or become a multi-millionaire by being stupid. Perhaps he simply hadn’t been paying attention, but whatever it was, this was no genuine case of naivety. On the contrary, it was a cynical pitch to susceptible rubes that they should keep watching and continue pumping their money into the coffers of a gigantic media corporation every bit as responsible as the Glazer family or John W. Henry for the current state of football, who in fact helped to monetise the game to such an extent that the attraction of pure-bred capitalists from every corner of the world to European football club ownership was utterly inevitable, in much the same way that you might get a few moths if you leave a light on and a window open during a summer’s evening.

I have no interest whatsoever in the concept of an ESL and I don’t support it in any way, but I was nonetheless sufficiently lucid to immediately recognise it as the inexorable conclusion of the path that football has been on for many years. I was also perceptive enough to identify many of the same ones shouting loudest earlier in the year as having been directly or indirectly involved in the descent of what may once have legitimately been “the beautiful game” into the degraded mess it has become. There are plenty who have long been blissfully happy to suckle at the game’s grotesquely bloated teat while telling the world that all was well. Now they were suddenly biting down, hard, at the threat of said teat being removed.

The one exception was the supporters, whether of the clubs involved or those further down the foodchain whose very existence continues to be threatened on a continual basis by the perpetual madness consuming the upper echelons of the sport. Their motivations were self-preservatory too in a way, given that football is their passion and that the only alternative to its modern variant would be to stop watching altogether, but they were also about the only party involved to show any sense of genuine naivety on the issue.

Admittedly, taking the most public protests against the ESL involving Chelsea and Manchester United supporters as an example, it was difficult to imagine naivety being much of a problem for a group who spent much of the 2019/20 season inventing reasons why Liverpool’s first league title in 30 years didn’t count and who for the past 7 years have taken great pleasure from memorialising a slip by a Liverpool player during a season where their respective clubs finished 3rd and 7th and won nothing. Where the naivety comes in is twofold: (1) believing that anything uttered by the likes of Neville is genuine, and it certainly looked as though they did given that the scenes at Old Trafford on 2nd May followed hot on the heels of his call for supporters to “mobilise”, and (2) the idea that such actions will change anything, at least in the longer term: they won’t.

Football has long since become a zombie version of the game we all love. In much the same way as the “walkers” in the Walking Dead still have two arms, two legs and a head (well, most of them), football continues to consist of two teams of eleven playing on a grass pitch in front of live spectators. It has a ball and two sets of goalposts, and the objective remains to put one through the other. The basic shell is still there, but underneath it has been a completely different creature for a very long time. I know that all too well; we all do, if we’re being honest with ourselves, but it’s not so easy for supporters to give up on something to which they, and very often generations of their families, have devoted their lives. It is that reluctance, largely driven by longstanding ritual and fear of the unknown but also genuine love, which allows this zombified version of the game to maintain its captive audience and con supporters into thinking that it remains worthy of their time and affection.

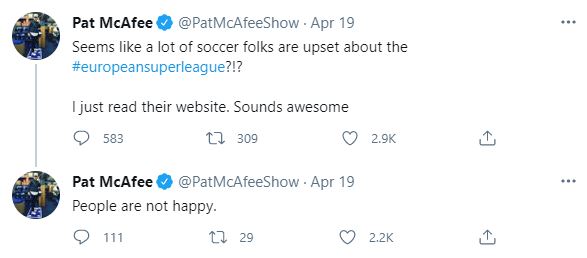

This is to say nothing of how the nature of “support” has changed. Former NFL punter Pat McAfee, who has become a successful sports analyst and podcaster since his retirement, suffered a significant backlash on social media following his initial comment that the ESL “sounds awesome”. Of course, from the point of view of an American “soccer” fan, it would: a globally televised NFL-style competition where the very best teams and players go up against each other on a weekly basis throughout the season, what’s not to love? He later apologised after a number of supporters “smartened me up” to the unique traditions of European football, but his faux pas is instructive of how international fans differ from their local equivalent in what has long since become a fully globalised entity.

The 12 clubs who attempted to form the ESL would have looked at the raw figures (e.g. the populations of Liverpool and Manchester numbering around half a million people each, with loyalties split between several different clubs vs. the estimated global fanbases of Liverpool F.C. and Manchester United which run into the hundreds of millions) and figured it was a no-brainer to prioritise the majority around the world who buy just as many jerseys and watch their teams on television with just as much religious fervour as the local fanbases but without the rigid adherence to tradition. If you understand that tradition, as the majority of local supporters do (“local” in this case being the longstanding support you find in Britain, Ireland and the Scandanavian countries, let’s say), then it’s anathema to go against it to such an extent; if you’re a fan based in Seoul or San Francsico who has never set foot on European soil and engages with the sport to a large extent through video games, fantasy football and social media, you might not care quite as much.

Whether we like it or not, the latter group now forms the vast majority of an elite club’s total fanbase and, accordingly, represents a far greater portion of its revenues than the supporters in the stadium on a matchday. This is a relatively new phenomenon only in so far as European club football’s globalisation is relatively new, kicking off in earnest in the 1990s, and is in stark contrast to the situation that existed for the first century or more of the English Football League, where matchday receipts were a club’s primary source of income. Go back to the 1980s, however, and look at what the likes of Martin Edwards (Manchester United), David Dein (Arsenal) and Irving Scholar (Tottenham Hotspur) were doing at their respective clubs, and tell me with a straight face that those (English) owners would have done it any differently to their modern equivalents if they’d had the choice back then.

There was a lot of talk in the weeks following the ESL announcement about owners, and the area of club ownership is certainly one in which the game has changed; but like everything else, it changed a long time ago. It goes back a lot further than the influx of foreign owners sparked by the arrival of Roman Abramovich at Chelsea in 2003, and it is by no means an issue confined to the six English clubs who tried to form the ESL: at the time of writing, only around a third (15 out of 44) clubs in the Premier League and EFL Championship are majority-owned by British citizens. And in any case, the assumption that the correct nationality automatically equals competent owners/executives who selflessly care about their club and its community is utter nonsense — just ask a Newcastle United fan. I sympathise with anyone who genuinely yearns for the days when there remained a chance that the owners of football clubs would have links to the community and a proper appreciation for tradition, but that ship has well and truly sailed.

In terms of when it sailed, that depends on who you ask and how shrewd a grasp of history they have. Speaking for myself, I could say it departed on 6th February 2007 when a couple of American speculators, Tom Hicks and George Gillett, purchased Liverpool. You could argue, however, that it actually set sail on 1st July 2003, when Russian billionaire Abramovich purchased Chelsea and embarked upon a level of transfer spending so unprecedented that Liverpool’s then-owner, Scouser David Moores, was left with the binary option of either operating an also-ran or moving aside for someone who could fund a successful 21st century football club (while Hicks and Gillett were certainly not the right men for the job, the source of his motivation to sell was obvious). Or I could go back further again, to June 1991, when Manchester United floated on the stock exchange for the first time and secured enough financial muscle to dominate English football for over two decades. Of particular interest to any Manchester United fans who may be reading: the other side of that coin was the arrival of the Glazer family 14 years later.

In the end, the supporters have been left to go through the normal motions of supporting their team in the knowledge either that their club is killing football or being strangled by it, the true victims not only of the greed shown by the sport’s richest clubs for decades but also the incompetence and cowardice of those entrusted to protect it on our behalf. Manchester United and Arsenal supporters are sure that anyone would be better than the Glazer and Kroenke families respectively, and are convinced that they’ll slay their golden goose for the right offer; conversely, Liverpool fans may be minded to look at a first league title in three decades, a new Main Stand at Anfield with further redevelopment imminent, a new £50m training facility and the remaining vestiges of Hicks and Gillett in the rear-view mirror and think it’s better to stick than twist at this stage, despite everything; and supporters of last season’s Champions League finalists Manchester City and Chelsea will simply continue to enjoy their respective lottery wins while blaming everyone else for the ills that continue to consume modern football.

As if any of it matters in this game of zombie-ball. To borrow a long-standing cliché, “the game is gone”, and I don’t recall any of the events which led to its demise being greeted with popular dismay at the time amongst those in a position to be heard and/or do something about it, be they the sport’s governing bodies, the players in the respective dressing-rooms up and down the country, or the pundits who inhabit TV studios from Isleworth to Salford. I am reminded of The Scorpion and the Frog fable: better not to allow your natural enemy to hop on your back in the first place than expect him to change his nature halfway across the river. The same individuals crying about the ESL in April were gleefully hyping and promoting every new development over many years, including the frequent arrivals of rich foreign owners, with barely a thought given to the long-term ramifications for English football as they wallowed in the muck of avarice. Suddenly, we find them bemoaning the greed being shown by the owners of the 12 clubs now, as if the mysterious motives of arch-capitalists have only just been exposed like a Scooby-Doo villain.

Well, fuck them. I didn’t buy a single drop of their crocodile tears, no more than I bought the apologies of the clubs themselves. At least their motives were clear, rather than this arse-covering hypocrisy arriving far too late to be worth a damn.

* * *

1983 was quietly a pivotal year for English football. On the surface, there was nothing out of the ordinary: Liverpool won two of the three domestic trophies on offer and the national team failed to qualify for a major tournament, all par for the course in that era (i.e. the Reds were in the middle of a run of three league titles and four League Cups in a row, not to mention four European Cups in 8 years, while England had now failed to qualify for four of the last six major international tournaments). There were several new developments, however, that would have far-reaching consequences. In many ways they laid the foundation for the decision, some 38 years later, of the country’s six richest clubs to break away from the UEFA Champions League to form their own exclusive competition:

- Tottenham Hotspur became the first English club to float on the stock market. The interesting part is how they did it. As set out by the Guardian’s David Conn in 2007, “the club’s advisers asked the FA if Spurs would be free to form a holding company to evade the FA’s restrictions on dividends and directors’ salaries. The FA, who have never explained why, permitted Spurs to do what they wanted. Every other club that floated after that formed holding companies similarly, to bypass the FA’s rules.” In other words, not only did Tottenham open themselves up to the possibility of private individuals investing in the club purely for profit in the future, and not only did they establish something of a guidebook for others to follow suit, they did so with the FA’s blessing.

- As alluded to above, Tottenham’s circumvention of the FA’s rules not only changed the structure of football club ownership, it effectively removed limits on remuneration of directors that had previously been in place. As set out by Conn (emphasis is mine): “The FA once took a robust view that clubs were not there for owners or directors to exploit. In 1899, just as professional, commercialised football was taking off, the FA imposed rules to protect the clubs’ sporting heart. These allowed clubs to form limited companies, but prohibited directors from being paid, restricted the dividends to shareholders, and protected grounds from asset-stripping. Later codified as the FA’s Rule 34, these restrictions established the culture that being a club director was a form of public service, that directors should be ‘custodians’, to support and look after clubs.” Rather than rewording Rule 34 slightly to take account of modern developments while retaining the spirit in which it had originally been conceived, the FA simply stood by and allowed its demise.

- Under pressure from what were then the country’s five biggest clubs (Arsenal, Everton, Liverpool, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur), the Football League members agreed to abolish the principle of gate-sharing that had been in existence to some degree since the formation of the Football League in 1888. At the time of its abolishment, 20% of gate receipts were being given to the away side and a levy of 4% (which remained) was being taken from all gate receipts and redistributed evenly between the 92 league clubs at the end of the season. The big clubs had effectively been subsidising the smaller ones with their larger attendances for years and, beginning in 1983, decided that enough was enough.

Ok, let’s back up here for a minute: how did these five clubs come to wield so much outsized power in the first place? Good question. That’s a longer story but we can trace some of its origins back to January 1961 and the abolition of the maximum wage in English football.

Now, this was certainly a good moment for the players and it’s impossible to argue against it in any meaningful way. However, with the restrictions lifted, a bi-product was that wages steadily increased over time to a point where the bigger city clubs with the larger catchment areas and stadiums, in an era where live attendances were a club’s main revenue source, were able to pay more and hence assemble better teams. As John Williams outlined in his book, Red Men: Liverpool Football Club: “The lifting of the maximum wage in 1961 and the challenges from the players’ union to the retain-and-transfer system that would finally succeed in 1963 promised more movement of top British players to football clubs that were free-spending, ambitious and progressive.” In other words, a club would now be able to attract more of the best players by spending more money.

As Four Four Two pointed out earlier in the year, a knock-on effect was a transfer of power away from provincial clubs as their players naturally went where the money was, leading to a less egalitarian system and the gradual development of a permament power base for a small number of “super clubs”: “This further strengthened the city clubs at the expense of the town teams, many of them Football League stalwarts, who now suffered a talent drain to burgeoning superclubs in major cities like London, Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds. Whereas the three previous league titles had gone to town teams in Wolverhampton (made a city in 2000) and Burnley, the provincial prowess promptly dried up. Since 1962’s surprise champions Ipswich, helmed by some tactical whiz called Alf Ramsey, only three of the subsequent 58 titles have gone to towns: Derby in 1972 and 1975 (shortly before it became a Silver Jubilee city in 1977) and Blackburn in 1995.” Even then, one of those (Blackburn) required a wealthy benefactor to buck the trend.

To put it another way: including the 1960/61 season, the first 62 League Championships since the inaugural season in 1888/89 (inclusive of breaks for the world wars) were split between 18 clubs. With Manchester City’s recent victory, 46 of the next 60 top flight titles have now been shared between just five, all of whom were amongst the six which attempted to establish the ESL in April.

As the landscape around football gradually evolved alongside increasing television coverage, the bigger clubs with the better teams were able to convert their success on the pitch into a wider fanbase, capturing the imagination of young, impressionable fans by reaching straight into their living-rooms. It has long since come as no surprise to any of us to hear of Manchester United-supporting Cockneys or, from personal experience, Chelsea fans from Ipswich. The big clubs were thus able to extend their supporter base far beyond the confines of their own local populations, and this arguably had an even more marked effect as club football began to globalise and merchandising really came into its own in the 1990s.

By the mid-80s, there was already an embedded hierarchy at the top of the English game and those clubs were only just discovering the extent to which they could throw their sizeable weight around. The lineage from April’s ESL announcement to the events of 1983 is unmistakeable: England’s most powerful clubs had scored major victories over both the Football League and the FA in quick succession, and their demands would gradually become more ambitious in the coming years.

By 1985, television revenues were in their sights. Similar to the 4% levy on gate receipts, the spoils from the sale of TV rights to the likes of BBC and ITV had hitherto been distributed equally amongst all 92 clubs in the Football League. However, these had become increasingly lucrative by the middle of the decade and, as such, came to be eyed jealously by the same powerful clubs. On that basis, in December 1985, the aforementioned “big five” of English football pushed through an agreement (the “Heathrow Agreement”) that would see First Division clubs pocket 50% of future television deals, with the Second Division getting 25% and the remaining 25% shared between the Third and Fourth. The levy on gate receipts was also reduced from 4% to 3%.

New television deals subsequently negotiated in 1986 and 1988 saw a substantial rise in revenues, aided by the rivalry that had emerged between BBC and ITV, and an ever-increasing proportion was hoovered up by the elite clubs. As noted by Matthew Taylor in his 2013 book, The Association Game: A History of British Football: “It is estimated that the ‘Big Five’ received just under a third (£3.5 million of a total £11 million) of the ITV money invested in the Football League in 1988-9.” Think about that for one second: 31.8% of the money went to 5.4% of the clubs. All of this was achieved under threat of a breakaway league, facilitated further by ITV’s militancy in negotiating directly with the big clubs. And if you want an idea of how real this threat was perceived by the mid-80s, consider the fact that football magazine When Saturday Comes published an editorial in June 1986 which contained a cartoon with the slogan: “STUFF YER SUPERLEAGUE!”.

Around the same time, Manchester United chairman Martin Edwards, who would ultimately net an estimated total of £93m from selling his shares in the club in the years immediately preceding the Glazer takeover, could be heard explicitly commenting: “The smaller clubs are bleeding the game dry. For the sake of the game, they should be put to sleep”. Proof, if it was needed, that the concept of greed at the “Theatre of Dreams” didn’t start with the Glazer family. In the face of such breathtaking arrogance, the ultimate goal of a breakaway league conceived to benefit the country’s biggest clubs was a hopeless inevitability. It eventually came to pass in 1992, when 22 First Division clubs broke away from the Football League to form the Premier League.

Initially, lest we forget, the new arrangement comprehended no sharing of money to the rest of the national game. Over the years, the game’s authorities have succeeded in negotiating some revenue distribution down the league pyramid, namely parachute payments (which, of course, are dependent on reaching the Premier League in the first place) and solidarity payments to the rest of the Football League clubs, but these are mere crumbs from the table compared to the situation that existed pre-1983. The initial £305m domestic broadcasting deal with Sky and the BBC in 1992 has now swelled to a monstrous £4.464bn split amongst 20 clubs, which doesn’t include similar astronomical figures being spent by international broadcasters. And unless you believe there is a reasonable chance that members of the current “big six” of Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham could ever be relegated, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the Premier League has been an elitist enterprise from its very conception.

Similar stories have played out in the two other countries that provided the 12 founding members of the ESL, namely Italy (AC Milan, Inter and Juventus) and Spain (Atlético Madrid, Barcelona and Real Madrid). The etymology of these clubs’ power and influence goes back a long, long way, with the exceptions of Chelsea and Manchester City whose tickets to the party were bought and paid for by foreign oil money in 2003 and 2008 respectively. Nothing here is new, not really. The 12 founding members of the ESL have won a cumulative 204 titles out of the last 301 in their domestic leagues, just over two-thirds in what is the equivalent timespan of three centuries. This staggering statistic (excluding seasons for which no title was played/awarded) is broken down as follows:

- England: Manchester United (20), Liverpool (19), Arsenal (13), Manchester City (7), Chelsea (6) and Tottenham (2) have won 67 of 122 league titles going back to the inaugural season of 1888/89 (of note, this figure rises to 76 of 122 if we include Everton who were one of the original “big five” in the 1980s before falling away in the Premier League era).

- Italy: Juventus (34), Inter (17) and AC Milan (15) have won 66 of 89 league titles going back to Serie A’s inaugural season of 1929/30. No club outside of this big three has won it since AS Roma in 2000/01.

- Spain: Real Madrid (34), Barcelona (26) and Atlético Madrid (11) have won 71 of 90 league titles going back to La Liga’s inaugural season in 1929. No club outside of this big three has won it since Valencia in 2003/04.

The ugly truth is that the history of English football, or at least the last 40 years of it, is littered with such examples of its most powerful clubs, be it a “big five” as it was in the 1980s or a “big four” as it became in the 2000s or a “big six” as it currently stands, coming together to lobby for their own blatant self-interest. Concepts such as breakaway leagues, lopsided distribution of wealth and just plain greed are nothing new; in fact, you might say they’re as English as the St. George’s Cross. The chief difference here appeared to be that the clubs in question were forming a competition outside of the country, although it should be noted that they outlined their intention to continue competing domestically as before: it was the Champions League they wished to quit. Nonetheless, all of the same characteristics were there.

Speaking of the Champions League…

* * *

Alongside their continental brethren, the same clubs have been a driving force over the years in the evolution of European football’s most prestigious club competition into the most elitist entity of them all, regardless of what UEFA would have you believe. Many of the same patterns are evident in the process whereby the European Cup, for over 30 years a straight knockout competition featuring the champions of every UEFA member nation, became expanded in 1991 into a mini-league format similarly designed to funnel more revenues to the biggest clubs and which was also established under threat of a breakaway competition. With English teams banned from Europe during its conception in the late-80s, however, it was the Premier League’s predecessor as the most powerful domestic league in the world, Serie A, where the seeds for change were sown.

Italian football certainly had reason to be disgruntled with the European Cup in the latter half of the 1980s, I’ll give them that. By that time, Serie A had unquestionably developed into world football’s most glamorous domestic competition. In an era when English football was mostly insular and closed-off to foreign imports, Italian football boasted international superstars like Diego Maradona, Michel Platini, Preben Elkjær, Ruud Gullit, Careca and Lothar Matthäus. The likes of Johnny Metgod and Nico Claesen didn’t really measure up in comparison (look them up). Alongside those global stars, you had wonderful homegrown talents like Paolo Maldini, Franco Baresi, Gianluca Vialli and Roberto Baggio. And it was competitive too: in the seven seasons from 1984/85 to 1990/91 (inclusive), there were six different Scudetto winners (compared to three winners of the English First Division).

In Europe’s most prestigious competition, however, it was often a different story: although AC Milan managed to claim back-to-back European Cups in 1989 and 1990, the same time period saw winners crowned from Romania (1986), Portugal (1987), the Netherlands (1988) and the former Yugoslavia (1991). What’s more, the interest of Italian champions in the competition was often short-lived and even a little embarrassing, hardly befitting the world’s greatest league. The nadir was unquestionably Inter’s first-round exit to Swedish champions Malmö in 1989/90, but there was also a first-round departure for Maradona’s Napoli in 1987/88 (to Real Madrid), as well as last-16 defeats for Juventus (to Real Madrid) and Napoli (to Spartak Moscow) in 1986/87 and 1990/91 respectively.

Silvio Berlusconi, then a media tycoon and entrepreneur who had purchased AC Milan in 1986, was horrified at such results. As he would later tell Keir Radnedge of World Soccer magazine in 1991: “The European cups have become a historical anachronism. It’s economic nonsense that a club such as Milan might be eliminated in the first round. A European Cup that lasts the whole season is what Europe wants.” Back in 1988, he had commissioned the advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi to draw up a blueprint for a “European Television League”. The agent who ended up with the commission later recalled: “He decided to publicise it and use it as a stalking horse and catalyst to support his argument…When someone like Berlusconi has a plan for a breakaway European super league, even UEFA had to sit up and take notice.”

And take notice they did: much as the threat of secession by English football’s “big five” had created the conditions for all other parties (i.e. the FA and the Football League) to acquiesce to revenue-sharing agreements against their own best interests and eventually the creation of the Premier League itself, so UEFA bowed to Berlusconi with the establishment of a new format beginning in the 1991/92 season, where two four-team mini-leagues would essentially serve as the quarter- and semi-finals rolled into one. It would be renamed the Champions League with effect from 1992/93.

The new format didn’t immediately make the bigger leagues bulletproof against early elimination, with the English (Arsenal), German (Kaiserslautern) and Dutch (PSV) champions all failing to make the group stages in 1991/92, and the English (Leeds United), German (Stuttgart) and, most shockingly, reigning Spanish and European (Barcelona) champions following suit in 1992/93 (from the Italian perspective, however, Sampdoria only had to defeat Norwegian and Hungarian opposition to make the group stage in 1991/92, and Milan the Slovenian and Slovak champions in 1992/93). Gradually, however, over time and with successive revisions to the format, Europe’s richest clubs have created a situation where:

- They are virtually certain of qualification to the Champions League each season, the one exception in Europe being the ultra-competitive Premier League. Beginning with the 2024/25 season, even that barrier will be reduced somewhat under a newly-agreed structure that will see two clubs with high UEFA coefficients entered in the competition where they have not already qualified via their domestic league. To borrow a phrase from American sports, these are effectively “wild cards”. Liverpool and Juventus, who spent much of last season outside of the top-four in their respective domestic leagues, would have had the safety net of this new loophole if it was currently in place.

- By simply qualifying, even if they don’t win the competition, they are practically guaranteed to play 8–10 games due to their relative strength, thereby consistently availing of lucrative worldwide television and sponsorship revenues on a yearly basis. By the same token, the group stage format typically allows the strongest to ultimately prevail despite bad days at the office: Real Madrid, who lost home and away against Shakhtar Donetsk in this year’s competition, recovered to reach the semi-final while their Ukrainian conquerors were dumped into the Europa League. All a far cry from Napoli in 1987 or Inter in 1989.

This system has evolved over three decades and has included many tweaks largely designed by UEFA to appease the big clubs, who were originally represented by G-14 from 1998–2008 and later the European Club Association (ECA). G-14 was essentially a lobby group, and while the ECA has expanded its membership to include over 200 clubs, the ongoing changes to the format of the Champions League over the years have consistently benefited the richest. Some of these have included:

- The introduction of a preliminary round in 1992/93, expanding to two qualifying rounds from 1997/98 and three from 1999/00, which have made it progressively more difficult for champions from weaker leagues to reach the lucrative latter stages or land a money-spinning tie against a major club.

- The steady expansion of the group stages, first to four groups comprising 16 teams (1994/95), then six groups comprising 24 teams (1997/98), then the eight groups of 32 teams we still have today (1999/00).

- The admission of non-champions from the strongest leagues, beginning with runners-up from 1997/98 and quickly expanding to third and fourth place teams from 1999/00.

Other initiatives over the years were scrapped but were no less indicative of the direction of travel. Only the top-24 national champions were allowed to enter for three seasons in the mid-90s, with the others dumped into the UEFA Cup, and for four seasons at the start of this century, beginning in 1999/00, a second group stage was added comprising the 16 best teams from the first one. Instead of 11, the minimum number of games required to win the competition had temporarily mushroomed to 17, all the better to generate increased television revenues. The format will change again from 2024/25 after a period of relative stability to a 36-team league system with a play-off round and the familiar knockout system from the last-16 onwards. It certainly doesn’t take a genius to figure out why a full league system is now being implemented, particularly since the reforms were announced by the UEFA Executive Committee on 19th April 2021, one day after the proposed ESL had been made official.

The introduction of more teams from the stronger leagues, coupled with the expansion of UEFA member associations (32 countries took part in the reconfigured competition in 1991/92, compared with 54 in 2020/21), means that the weaker leagues have almost entirely been squeezed out. For the 2020/21 season, 79 teams competed for just 32 spots in the lucrative group stages of the competition; however, 26 of these were automatically taken, including a combined 19 by Europe’s five strongest leagues (Spain, England, Italy, Germany and France). From there, 53 teams played off for just 6 places. Essentially, this represents a 1 in 9 shot of making it, but taking into account the fact that relatively well-funded clubs from leagues like Greece, Portugal, Russia and Ukraine would have awaited the likes of Dundalk (Republic of Ireland) or Djurgårdens IF (Sweden) if they made it that far, the odds are likely to be even longer.

Which is fair enough, you might argue. The only reason the Champions League became a golden goose in the first place is because supporters all over the world want to see the very best clubs and players going up against each other. Who gives a fuck about Dundalk or Djurgårdens when it’s the biggest clubs on the planet that drive global interest in the product and entice TV broadcasters into parting with large sums of money to cover their matches, right? Well if you believe that, then the ESL should be right up your street, shouldn’t it? This logic ignores UEFA’s stated obligations to its members and its related culpability for allowing the richest leagues and clubs to dominate their marquee competition for so long that not only have the strongest become even stronger, the weak have weakened further to the point where the vast majority of UEFA’s national champions are no longer capable of even drawing a sweat from the bigger clubs on the rare occasions when they get the chance.

Take a country like Sweden, whose current national coefficient puts their champions squarely in the first qualifying round for the Champions League. As we have seen, Malmö were able to humble Serie A giants Inter in 1989, a team that included a host of players who would feature/star at Italia ‘90 the following year (Walter Zenga, Giuseppe Bergomi, Riccardo Ferri, Andreas Brehme, Lothar Matthäus, Jürgen Klinsmann, Aldo Serena). This came just over 10 years after the same club had reached the final itself, going down 0-1 against Nottingham Forest in Munich, and in the same decade where compatriots IFK Göteborg had won two UEFA Cups (in 1981/82 and 1986/87). And in the early years of the Champions League, the latter were also able to top a group that included Barcelona and Manchester United (1994/95), thereby knocking out the English champions.

The last time a Swedish side made a splash in the competition was also against Inter, when Helsingborgs knocked them out in the third qualifying round in 2000/01; but in the twenty seasons since then, a Swedish team has made the group stages of the competition precisely twice: Malmö, in 2014/15 and 2015/16. On both occasions they finished bottom of their group, with a combined record of: P12 W2 D0 L10 F5 A36. The last game a Swedish side played in the richest club football tournament in the world was on 8th December 2015, when they went down 8-0 in the Santiago Bernabéu.

Or what about Scotland? There is a savage irony in the fact that Glasgow Rangers were intimately involved in the creation of the Champions League format, via club secretary and future Scottish FA president Campbell Ogilvie. “Domestically, there was a ceiling. And in Europe, you could be out after one round. I remember we played Osasuna in 1985/86 and went out. That spurred on discussion for all clubs of our size – how do we take this forward? Can we get European football into some sort of structure where we could at least be guaranteed six games, three of them at home? That was where it started from.” It certainly went well for them at first, taking eventual champions Marseille to the limit in 1992/93 and coming close to making the final against AC Milan, but by the second half of the 1990s they had been unceremoniously dumped into the qualifying rounds of the competition and all subsequent Scottish champions have been hamstrung accordingly.

Today, it is no longer a given to find a Scottish club in the group stages of the competition, the last being Celtic in 2017/18. When they do make it, their consistent absences and the gradual denigration of their domestic league over a period of years has rendered them thoroughly unable to make a mark: Celtic’s 7-1 loss in Paris on 22nd November 2017, following on from a 0-5 home defeat to the same team earlier in the competition, was nothing short of a humiliation for a club that had reached the final in 1967 and 1970, winning the former, and a country that had provided UEFA Cup finalists as recently as 2003 (Celtic) and 2008 (Rangers). Ogilvie ultimately got his wish: Rangers would have been “guaranteed six games, three of them at home” if Steven Gerrard’s men could have navigated their way through their recent qualifying round against, ironically, Malmö. But they didn’t, and so Scottish football’s absence from European football’s showpiece competition will continue for another season at least.

You can repeat this trick around Europe, incidentally, go country by country outside of the top five leagues. Perennial Portuguese champions FC Porto were at least automatic qualifiers for the 2020/21 group stages, and were able to navigate a group that included Manchester City all the way to the quarter-finals, knocking out Juventus along the way. But the Deloitte Football Money League, published in January 2021, puts them outside the top-30 clubs in Europe for revenue, behind the likes of Crystal Palace, West Ham United and, most damningly of all, Sheffield United. What reasonable chance exists that the European champions of 1987 and 2004 will ever even reach a final again, much less win it?

And all the while, the richest clubs continue to push for more and more, even going so far as to plead comparative poverty with a straight face. If Serie A was where the impetus for the Champions League arose, it continues to be a prime source of agitation for a new structure that favours the powerful to an even greater degree. With Berlusconi gone (the biggest irony of all being that even his beloved AC Milan eventually fell foul of the new format, having only recently qualified for the competition again for the first time since 2013/14), Juventus chairman Andrea Agnelli has now taken his place as the visionary who refuses to keep his visions to himself.

With the £4.464bn deal for domestic TV rights agreed by the Premier League for the period 2019–2022 dwarfing the €2.5bn (around £2.1bn) recently agreed by Serie A for the period 2021–2024, and no Italian club appearing in the top-10 of Forbes’ 2021 list of richest clubs, Agnelli’s plan seems to be based around dragging the big English clubs as deep as possible into a pan-European competition where his own club can grab an equal share of the spoils. He was quoted as saying the following in 2019: “What we felt was important for us is if we want to create a platform that allows for all clubs to succeed on and off the pitch more European football is good for the game.” And before that, in 2018, stressing the need for “…more international exposure, to develop our brands. Today everything is about brand exposure.” The proposed model of the ESL would certainly put his club on more of an equal footing with their Premier League rivals on that basis.

* * *

I could continue talking about how English and European football has developed over the past 40 years forever, but let’s take a momentary break for reflection here. Suffice it to say that all of the above events happened, and they tell a tale. They tell the same tale as the one told in a joint statement dated 18th April 2021 by UEFA and others (the English FA and Premier League included) on the subject of the ESL that spoke of a “cynical project, a project that is founded on the self-interest of a few clubs at a time when society needs solidarity more than ever.” A statement that went on to say that “football is based on open competitions and sporting merit; it cannot be any other way…This persistent self-interest of a few has been going on for too long. Enough is enough.”

As a football supporter of some 35 years’ standing, of Liverpool and the Republic of Ireland specifically, I cannot argue with the sentiment expressed by those words; I can, however, pour scorn upon the ones saying them. In April 2021, 30 years after the reconfiguration of the European Cup into a league format to appease Silvio Berlusconi and 29 years after the Premier League was established with the full blessing of the FA to similarly mollify England’s richest clubs, during which time the only prospect of less powerful clubs ever rising to compete with the elite has become distilled down to the vague possibility of being taken over by a billionaire foreign owner, apparently these governing bodies were suddenly taking a stand against the cynical, self-interested greed of the few in favour of open competition and sporting merit.

Somehow, even accepting that the ESL represented repugnant new depths of elitism, it was the sheer, brazen chutzpah of these governing organisations that most disgusted me in the aftermath of the announcement. The obvious question that immediately arose, for me at least, was why now, when they never gave a shit before? Well, the answer is relatively straightforward: their share of the cut.

Back in July 2019, UEFA estimated that the gross commercial revenue from the 2019/20 Champions League, Europa League and Super Cup would be around €3.25bn. Of that total, only 7% (€227.5m) was to be set aside for solidarity payments to the hundreds of clubs and dozens of leagues across Europe who have become de facto non-runners in 21st century European club football. Of the net revenue remaining following the deduction of those meagre solidarity payments and organisational/administrative costs (€2.73bn), 6.5% (around €177m) would “be reserved for European football and remain with UEFA”. The total pot for participating clubs in the Champions League was set at €2.04bn, so UEFA’s cut of the big clubs’ money was in and around 8.5%. That’s not a bad return considering Walter White’s fixer (Saul Goodman) was only getting 5%. In any case, they earned it: the last-16 of the 2019/20 competition was comprised solely of teams from Europe’s top-five leagues and included 8 of the 12 ESL founders, so that’s where the bulk of the money went.

Aside from the tiny solidarity payments designed to give the faintest impression possible of a governing body caring about the welfare of its members, and the €300m or so paid out to the clubs eliminated in the group stages and qualifying rounds, there isn’t much more UEFA can do for the richest than they already are. But now the same clubs were looking to essentially cut out the middle man, take the £3.5bn supposedly on offer from JP Morgan bank for their proposed new league, cut their own TV deals and split the proceeds 12 ways (or 20 if you include the invitees and qualifiers to be added at a later date). The plan had obvious implications for the prestige of UEFA’s flagship competition, with a resulting fall-off in commercial revenues almost certain to follow as the worldwide TV audience follows the big boys to their new playground, and it’s hard to imagine sponsors like Gazprom and Playstation not doing similar in order to get as many eyeballs on their product as possible. What would UEFA’s annual 8.5% cut be worth then?

It was a similar story for the Premier League. At no point since its conception some 30 years ago has the organisation shown a similar level of condemnation for the cynical, self-interested greed of its own members or explicitly exalted the spirit of open competition and sporting merit. For example, it had very little to say back in 2002 when Manchester United chief-executive Peter Kenyon suggested that English football should be reduced from four professional divisions to two; and when “Project Big Picture”, allegedly the brainchild of Liverpool and Manchester United, surfaced last year and proposed amongst other things reducing the number of teams in the Premier League (20 to 18) and the Football League (92 to 90), handing full control of the Premier League to the nine clubs who have been in it longest, abolishing the League Cup, and adding a Premier League side to the Championship play-offs, all it could say was that “this work should be carried out through the proper channels enabling all clubs and stakeholders the opportunity to contribute.”

Right, because that’s worked so well in the past, hasn’t it? It worked wonderfully in 1983 when the sharing of gate receipts was abolished, in 1985 when television revenues were skewed towards the First Division for the first time, in 1986 and 1988 when the top clubs negotiated themselves an even bigger piece of the pie, and in 1991 when the First Division clubs formally agreed to break away from the Football League. A scenario whereby other parties, be they clubs or governing bodies, have to make a decision with a metaphorical gun held to their collective head is unlikely to produce an outcome with any democratic or fraternal merit whatsoever, and with Football League chairman Rick Parry (coincidentally or not, the chief executive of the Premier League upon its launch in 1992) supposedly in favour of the new proposals, the 72 league clubs outside of the top division are already fighting a losing battle from within.

So why the big reaction from the Premier League now, when their previous actions have shown such little evidence of ever caring before? Well, if you think about it, the organisation has suddenly found itself in a similar position to the Football League in 1991: the ESL is the Premier League to its Football League, if you will. Oh sure, the rebellion was limited to six clubs rather than 22 as it was in 1991, and those clubs outlined their intent to continue playing in their domestic league. Nonetheless, its most powerful and recognisable members were about to commit to another competition, and in an era dominated by television revenue the ESL represented an obvious rival both to the current domestic broadcasting deal of £4.464bn and, perhaps especially, the international rights. And while the six ESL clubs were to remain in the Premier League, at least in the short-term, there are only so many TV rights packages that the likes of Sky, BT and Amazon can purchase. If those companies were to feel that the ESL represented a safer bet to secure subscribers and advertising revenue, then that’s the route they would go. In other words, the gravy train could be grinding to a halt.

The FA, who honestly knows? This is an organisation that allowed one of its clubs to circumvent its own rules with no explanation in 1983, a decision which set the scene for many of the ownership issues we see in the English game today (more on those later), that gave its blessing to the creation of the Premier League, that allowed the holders of its most famous trophy to pull out of defending it in 2000 so they could go and play in FIFA’s pet tournament in Brazil as part of a cack-handed attempt to land the hosting rights to the 2006 World Cup, that was all set to sell its own national stadium to a foreign businessman (Shahid Khan) in 2018 before a parliamentary select committee got involved. Maybe they’re just incompetent? One thing is for sure, they haven’t made as much money as the others out of football’s steady degradation over the years, which makes you wonder why they’ve been such enthusiastic partners in the enterprise.

All of these entities, on the evidence of the past 40 years which has been outlined at length over the preceding 8,500 words or so, were thoroughly complicit in the decision of AC Milan, Arsenal, Atlético Madrid, Barcelona, Chelsea, Inter Milan, Juventus, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, Real Madrid and Tottenham Hotspur to propose this NFL-inspired competition with no relegation or promotion, which would give them the ability to negotiate commercial and broadcasting deals without any outside interference from governing bodies and split those revenues between the minimum number of partners required to make an effective product (honestly, if Barcelona and Real Madrid thought that “the market” would support 38 El Clásicos a season, it would have been a two-team league). This has been inevitable for many years due to the thirst for money coming from the top of the game, and the sad truth is that this hunger was never going to be permanently satiated with piecemeal concessions, not when simple mathematics continues to illustrate that the cut of sums like £4.464bn and €3.25bn is a lot greater the fewer the parties involved.

In 2019/20, Premier League champions Liverpool received a total of £134.1m from television revenues, inclusive of their equal share of £31.8m from the domestic TV deal, an extra facility fee depending on how many times they were broadcast of £31m, and £71.3m in overseas TV income. By contrast, according to the NFL’s new television deal announced in March, each team is projected to receive $321m (about £230m) per season from the domestic broadcasters alone. And it goes without saying that Association football is a far more global phenomenon than its American counterpart, meaning that an ESL done right could potentially be even more lucrative.

A key difference between the two sports, however, is that the NFL has never been anything other than a closed shop: it distributes power equally between its teams, whether in the form of salary caps or the weaker teams getting first pick of the best collegiate prospects in the annual NFL draft, but its mammoth revenues are split between a limited number of “franchises” who will never be relegated. The NFL Commissioner’s job is to look after the interests of these 32 teams (“protect the shield”, as he calls it), all of whom are “elite” sporting organisations by virtue of their very presence in the NFL. Entities like UEFA and the FA have a far greater number of interests to protect: 55 member nations and thousands of football clubs in UEFA’s case, 92 league clubs and a vast non-league system in the FA’s, the overwhelming majority of whom are not particularly profitable and represent specks of dust compared to the 32 NFL teams and the 12 ESL founders.

These organisations have summarily failed in their (admittedly onerous) duties by consistently adopting a policy of appeasement towards the same “few clubs” going back decades, in the vain hope that their concessions would prove enough to satisfy them. Well, just as the same policy utterly failed in preventing war in 1930s Europe, the governing bodies of European football have created a mess by taking the easier option at every turn while telling themselves and everyone else that the evolution of the game has been collaborative. In reality, it has been about as collaborative as any con: “Con schemes have characteristics of both trade and fraud. Like trade, cons are voluntary exchanges, and, like fraud, cons are voluntary exchanges induced by misleading representations. Fundamentally, cons further voluntary exchanges that are not mutually beneficial.”

Essentially, football’s governing bodies have been victims of a long con in which they were only ever complicit in so far as the conmen wanted them to be. Their ultimate mistake was believing that: (a) they were equal partners in the enterprise, and (b) the partnership would be a permanent arrangement. Cons, even long ones, eventually end, namely when the “rube” is of no further use to the con-artist. This is fundamentally what the ESL represents: the end of one con, and the attempted beginning of another. UEFA, the FA and their fellow national federations have been victims for a very long time. Even the Premier League, itself a willing participant early on, was just as naive as any of them in the end, a mere host body to which the parasites could attach themselves until a tastier meal came along.

* * *

The business of football has never held much interest, if any, for supporters of the so-called “beautiful game”. Of all the quotes attributed to Liverpool legend Bill Shankly over the years, one of the most evocative and fondly-remembered is when he posited that at “at a football club, there’s a holy trinity – the players, the manager and the supporters. Directors don’t come into it. They are only there to sign the cheques.” All club rivalries aside, your average football supporter would likely remain in full agreement with that sentiment today, even at a remove of several decades. They’re wrong, of course; maybe not back then, when the FA’s Rule 34 was in effect, but they most certainly are now. In fact, these days it’s about as dated a notion as women belonging in the kitchen or the potential for human colonies on the moon.

Although it outwardly appears to have escaped the attention of many, perhaps selectively so, football has changed drastically since Shankly uttered those famous words. Nowhere is this more evident than in the boardrooms of football clubs, and more specifically in the relationship between those who inhabit them and the other members of that famous “trinity”. At their most benevolent, owners and directors now have the power to catapult football clubs to permanent global success and stature; at their most incompetent and/or ruthless, those same boardroom suits possess the capability to humble and even outright destroy institutions that, in some cases, have been around for over a hundred years. What’s more, this is absolutely not a recent development.

Thrown into a time machine and catapulted 50 years into the future, I wonder what Shankly would make of a club like Leeds United, for example, one of Liverpool’s greatest rivals during his time in charge who have only recently returned to top-flight football after a 16-year absence following the cataclysmic events wrought by the mismanagement of a businessman in a suit?

Conversely, what would he make of Roman Abramovich’s influence at Chelsea? Prior to the Russian billionaire’s arrival at Stamford Bridge in 2003, the club had won a single league title in its history (in 1955, when Shankly was still at Workington), had never been anywhere near a European Cup/Champions League final, and had been bought for £1 (not a typo) as recently as 1982. Indeed, the last time a breakaway league was plotted to benefit a small group of elite clubs, in October 1990 when the managing director of London Weekend Television met with representatives of the “big five” clubs (Arsenal, Everton, Liverpool, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur) to discuss what would subsequently become the Premier League, recently-promoted Chelsea were on the outside looking in. Just over 18 years after Abramovich’s arrival, and three decades or so since the Premier League’s formative steps, the club is now sufficiently mammoth to have become one of the 12 founding members of the proposed ESL, very much a member now of an exclusive cadre of “super clubs” looking to create a closed shop where maximum revenues are shared between a minimum number of beneficiaries in perpetuity.

Most of all, what would Shankly make of his own beloved Liverpool, I wonder? When Abramovich first arrived in west London in mid-2003, the club was still owned by a Liverpudlian with an intimate familiarity and deep affection for both the city and the club (David Moores). Less than 4 years later, Moores would sell to foreign (American) investors citing a compulsion to “sell my shares to assist in securing the investment needed for the new stadium and for the playing squad”, investment he was patently unable to provide or develop himself.

One of English football’s crown jewels, Liverpool Football Club, had thus been sold to foreign speculators as a theoretical means of enabling the club merely to compete in the upper echelons of 21st century football, a new reality which had been driven to a large extent by the outrageous spending that Abramovich had embarked upon during his first few years at Chelsea. And while buyers Tom Hicks and George Gillett were certainly not the right people for the job at hand, the criteria for making that decision were crystal clear: already approaching 17 years without a league title, the club was in mortal danger of being cut permanently adrift if a suitable level of investment was not found. Just over 14 years later, the current owners of Liverpool, Fenway Sports Group (FSG), are only in that position because of David Moores’ fateful decision to sell in February 2007.

As previously stated, the business of football has traditionally held very little interest for fans of the game. Yet there I was, like thousands of Liverpool supporters around the world in the autumn of 2010, closely following Tom Hicks’ feverish attempts to convince a litany of financial institutions and hedge funds to help him pay off the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) loan which he and his partner, George Gillett, had used to purchase the club in a leveraged buyout in 2007. The global financial crash of 2008 and subsequent bailout of the banking sector meant that RBS were now under public ownership and, at least temporarily, were no longer in the business of accruing toxic debts from desperate speculators. The bill was coming due in October 2010.

Like many others I’m sure, the Hicks and Gillett era was literally the first time in my life that I had heard the terms “hedge fund” or “leveraged buyout”, and being forced to learn of them through football was utterly heartbreaking. A supporter since the 1986/87 season, I had scarcely read a single figure from the club’s annual financial statements in the decades prior to their arrival, nor had I ever experienced a club official arrogantly referring to himself in terms like “the Fernando Torres of finance”. This prolonged and visceral peek behind the curtain at the real business of 21st century football, the sordid fine print lurking beneath the vision of “the beautiful game” still being sold by the Premier League, Sky and others with a vested interest in perpetuating it, changed everything. You don’t recover innocence, it doesn’t regenerate like leaves on a tree. Once it’s gone, it stays gone.

I was reminded of that again in the aftermath of Sunday 2nd May, when a few hundred Manchester United supporters invaded Old Trafford in protest at the Glazer family ownership of the club and caused their Premier League game with Liverpool to be postponed. One tweet I read from a United supporter illustrated just how similar a path English football’s two biggest clubs have walked since the first decade of the 21st century:

Déjà vu. This is eerily similar to the manner in which Hicks and Gillett purchased Liverpool and sought to run the club during their brief time in charge. The crucial difference for Manchester United is that the Glazers never had to refinance their leveraged buyout or attract new investment to pay off a bank loan that was coming due in the aftermath of a global financial crash. The club was such a goldmine by 2005 that its own revenues paid for everything, including interest payments. Liverpool, by contrast, was still being run like a provinical operation when the club’s first American owners arrived, with a commensurately meagre income relative to the likes of Manchester United. This was, in fact, one of the main reasons Moores had to sell in the first place: he possessed neither sufficient personal wealth to fund a successful modern football club himself, nor the expertise to truly exploit the club’s name and increase its revenues accordingly.

And so, when push came to shove for Hicks and Gillett, they had no choice but to seek further investment from third parties. The subsequent action from the supporters when this became public, which included bombarding potential investors with emails, and the fact that RBS was now in public ownership with a different set of business practices, combined to ultimately purge them from the club, the result of a lucky convergence of circumstances. Their successors, FSG, while consistently falling someway short of perfect, have at least done what their predecessors during the Premier League era could not and exploited the club’s global brand value to the fullest extent in much the same way as Manchester United did in the 1990s, with Liverpool now the fifth most valuable football club in the world according to Forbes, just behind their bitter rivals.

Manchester United, whose development in this regard pre-dated Liverpool’s by about 25 years, were not so lucky. Aside from the fact that it was already sufficiently wealthy to fund itself, the messages coming from those inside the club with the power to resist the change of ownership in 2005 only compounded matters further. Most pertinently, Alex Ferguson routinely defended the Glazers during his time in charge. In 2006, his first public pronouncements about his new employers indicated that: “I have found them, without question, to be excellent new owners. They have never failed in their promises and their support in everything we have done.” In 2010, he reiterated that: “We have a great relationship, they never bother me, they never phone. They never interfere. What more can you ask for?” And in 2012, he stated: “I am comfortable with the Glazer situation. They have been great…When the Glazers took over here there was dissatisfaction, so there have always been pockets of supporters who have their views. But I think the majority of real fans will look at it realistically and say it’s not affecting the team.”

Compare this with then-Liverpool manager Rafael Benítez, who as early as November 2007 was outing the new owners’ lies (i.e. “If Rafa said he wanted to buy Snoogy Doogy we would back him”) during a surreal press conference in which the Spaniard repeated “As always I am focused on training and coaching my team” in response to every question from reporters, having been told by his employers to forget signing anyone in the January transfer window and work with the players he already had. Although Benítez received quite a bit of criticism from the football media afterwards, such was his relationship with the supporters that his actions unquestionably had a direct influence on the process by which Hicks and Gillett were eventually removed from the club. Manchester United, via Ferguson’s inaction, were rewarded with a further 5 Premier League titles following the Glazers’ takeover, as well as 3 Champions League finals, but looking at the scenes from Old Trafford in May, you wonder whether it was truly worth it.

Of course, both men had their own reasons for their respective responses. Benítez simply wanted the funds to compete on the pitch, and Ferguson clearly enjoyed the autonomy he was given over transfers and team affairs. It should be noted too, however, that Ferguson’s falling out with Irish racing tycoons John Magnier and JP McManus over the disputed rights to stud fees for the racehorse Rock of Gibraltar had a direct bearing on the duo later selling their 25.49% stake in the club to the Glazer family. Not only did the deal rid him of a significant thorn in his side, one which had publicly questioned Manchester United’s secretive transfer dealings in a letter to the board in 2004 and ultimately caused Ferguson’s son to be banned from representing any further players at the club, it came at a time when it certainly wasn’t in the manager’s interests to rock the boat with the team going through a transitional period on the pitch.

I guess we all have our vested interests, don’t we? I’ll always remember Match of the Day on 3rd October 2010, the day Liverpool slumped to a 1-2 defeat at home to Blackpool and slipped into the relegation zone amidst fan protests in the stands and outside the ground. At the start of a monumental month that could have seen our beloved club, at that time 118 years old, be placed into the grip of administration, the fans were desperate for someone, anyone, to help. Videos surfaced online to which a few individuals with a profile contributed, the likes of Ricky Tomlinson and John Aldridge, but a world-famous show on national television hosted by a Liverpool supporter (Colin Murray) and with a true Liverpool legend (Alan Hansen) on the pundit’s panel would surely tell the world the truth about what was happening at Anfield, especially now that it was all out in the open.

You would think that, wouldn’t you? Alas, Hansen’s reaction to Liverpool’s plight was to say “forget the manager, forget the owners”, having himself spent much of the previous year going after former manager Benítez. And Murray, whether under instruction or not, drew a withering comparison between Liverpool’s protesting supporters and their counterparts from Blackpool, who were happy to sing and support their team win, lose, or draw: “they’re just awesome”, he gushed. Inside the club, new manager Roy Hodgson was his typical selfish self (“The protest does not help but it is something I have had to live with since I came to the club”), and both captain Steven Gerrard and vice-captain Jamie Carragher, from Huyton and Bootle respectively, preferred to concentrate on their football rather than the potential demise of their club, as later recounted by goalkeeper Pepe Reina:

“I was probably one of the loudest objectors because I believed it was important the supporters knew I was with them. All I wanted the owners to do was sell up to people who could take the club forward, so I said so. The way I saw it, Stevie and Carra are the two principle members of our squad, the ones who the people love and if they had said something maybe it would have put Hicks and Gillett under real pressure. But in their view, it was more important to try to keep things as normal as possible.”

How strange it was earlier in the year to hear Carragher, in his new career as a Sky Sports pundit, drawing comparisons between the Liverpool protests in 2010 and what happened at Old Trafford on Sunday 2nd May, given how silent he was at the time when it mattered. I wonder if Manchester United supporters felt similarly about Gary Neville and Roy Keane, both of whom were particularly sympathetic towards the supporters who protested at Old Trafford that day? Keane, who was captain of the club when the Glazers took over in 2005 but left a short time later, said the following: “The leadership of the club has not been good enough. When they look at the owners, they feel it’s just about making money. The United fans have looked at the Glazers and thought enough is enough.”

Meanwhile, Neville, who played under the Glazers from their arrival in 2005 until his retirement in 2011, went further, detailing how the club has deteriorated on their watch: “You look at the club now. This stadium, if you go behind the scenes, is rusty and rotting. The training ground is probably now not even in the top five in this country. They haven’t got to a Champions League semi-final for 10 years and haven’t won the league for eight years. The land around the ground is undeveloped, dormant and derelict when every other club seems to be developing their facilities and their fan experiences. The Glazer family are struggling to meet the financial requirements and the fans are saying the time is up. They’re going to make a fortune if they sell this football club. If they were to put it up for sale now I think the time would be right and it’d be the honourable thing to do.”

Like Carragher with Hicks and Gillett, both Neville and Keane have been conspicuously quiet on the subject of the Glazers over the years. Neville, who has since gone on to become arguably the most high profile football pundit in the history of televised English football, admitted as much earlier in the year, saying: “I’ve stayed quiet over the Glazer family on the basis that it’s still Manchester United, I can still watch them play, I can still be happy and sad. If they take dividends out, I can live with that slightly.” And in his second autobiography, published in 2014, Keane recounted what the Manchester United dressing-room thought of the Glazer takeover back in 2005: “From the players’ point of view, it didn’t bother us too much. I had a few shares in the club as part of my contract. So the Glazers coming in was worth a few bob to me.”

Over on Sky’s rival channel, BT Sport, another couple of Manchester United legends who would have been inside the dressing-room in 2005, Rio Ferdinand and Paul Scholes, were telling a similar story. As a means to illustrate the deception that had taken place from the very start, Ferdinand even pulled up a quote from Joel Glazer from 2005 referring to the supporters as the “lifeblood” of the club and highlighting the importance of communicating with them, communication which has scarcely taken place in the 16 years since. Ferdinand went on to say of the Glazers that “they thought they were buying a franchise” but didn’t realise that Manchester United is “a club that is steeped in history and a huge part of that is being part of the community”. Scholes, who it was acknowledged is Manchester born and bred, noted “the club going into massive debt” under the Glazers and, regarding the supporters, that “they’ve been desperate for 16 years”.

Neville, Keane, Ferdinand and Scholes were senior players at the club in 2005, one of them the captain. And as the Guardian’s David Conn has pointed out, there were plenty of supporters protesting then too, loud enough so that anyone involved with the club would have been hard pushed to ignore it: “The United protesters included corporate lawyers and accountants, and political activists who take heartfelt pride in Manchester’s radical traditions, and they patiently explained it. This was a leveraged buyout: the Glazers would not put a cent into United, but would want fortunes out.” Exactly what those individuals were alluding to now, albeit 16 years later.

Nobody listened then, when it mattered, least of all a dressing-room that included the same four individuals. They could have spoken out then, perhaps done what Reina would subsequently do at Liverpool five years later in the hopes of putting the current shareholders “under real pressure” not to sell. Instead, Keane, already a multi-millionaire in 2005, would glibly recount as recently as 2014 that he made “a few bob” out of it. And then Neville has the nerve to suggest that the current players should should make a stand: “I can’t sit here and say to the players of Liverpool and United to go on strike because that wouldn’t be right, but lads, if you’ve got it in you, you can stop this, you can mobilise it.”

Meanwhile, Carragher said the following about FSG in the aftermath of the ESL announcement: “I actually think the situation with Liverpool’s owners is that l don’t see how they can continue. They can’t just leave the club, obviously, the business is worth a lot of money. But I don’t see a future for the ownership of FSG at Liverpool on the back of this. This will never be forgotten. I think the best thing for them would be to find a new buyer. I think it will be very difficult for them to have any sort of relationship with Liverpool supporters and the club going forward.”

As I said, we all have our vested interests. Carragher, Keane, Neville, Ferdinand and Scholes were players when the aforementioned deals were taking place and likely had their own reasons for staying quiet then. For example, 32 year-old Carragher was in talks over a new contract during the crucial period of 2010 (September and October), while Keane admittedly made a few quid on the Glazers’ takeover. And you could certainly argue that sticking your neck out on issues like this as a player would carry with it the fear of being labelled a troublemaker and losing the trust of your manager, perhaps even being quietly moved along, although I would suggest that the age profile and critical importance to the team of Neville, Ferdinand and Scholes would have rendered that possibility unlikely. But what about their careers as pundits, when such possibilities no longer existed?

Since they left the club, when have those same ex-players ever spoken with as much concern about the Glazers as they did in April and May? Neville has been on Sky and Keane on a number of channels (on and off) since 2011, while Scholes and Ferdinand have been on BT since 2014 and 2015 respectively. All of a sudden they were going back over 16 years and highlighting everything the owners have done wrong, in 2021. Why weren’t they saying anything over the previous decade or so, as the Glazers publicly heaped debt on the club and the stadium began to show its age? Why not then? Instead, as recently as 2019, Ferdinand was in talks to become the club’s Sporting Director under the Glazers (“Manchester United and the powers that be will decide as and when they are going to put someone into that role. If I am the person on that list and the person they are going to talk to, then that time will come. It’s nice to be on a list in such a responsible role at such a prestigious club”).

I do wonder if it stuck in the craw just a little bit for Manchester United supporters to hear several of their legends who were at the club in 2005 suddenly decrying the Glazers, when realistically the ship has long since sailed for them in terms of owners with links to the community and a proper appreciation for the traditions of football. Much like Carragher to me, surely anything they say now is worthless, regardless of how loudly they say it?